The recent public outcry surrounding Cambridge Analytica and its use of massive amounts of personal data culled from Facebook triggered a global awareness of the unsuspected power of databases - especially the amount of data that is being collected and stored about every single one of us. Public comments followed on the appropriateness of collecting so much information and the ethical guidelines that should govern these practices.

Despite the brutal awakening for some and the knee-jerk reaction by others to curb the practice, data collection is not about to stop. Regardless of the eventual regulations imposed, the collection of personal data is bound to accelerate exponentially in the coming years.

People leave a trail with every purchase, every web search. Soon, many of their appliances will also transmit data about their usage (The Internet of Things). Database servers are fed continuous digital streams of data about our individual transactions and web behaviour. The infrastructure is in place. It works perfectly and nothing is going to stop it.

For the time being, in Western democracies, data is being collected primarily about consumption. Companies are targeting their customers to better understand them and ultimately offer them appropriately customized offers. (There is no doubt that people in their role as citizens won't be far behind!). These practices derive their legitimacy from personalization: data is collected on your preferences in order to present you with relevant offers and content perfectly matched to your lifestyle. Relevance is the key; it is the "cement" of engagement.

Nevertheless, we were curious to see what consumers thought about being continually "spied on" electronically! Since the subject is complex and required some nuance, we asked the question in the following way, with a preamble:

Digital technology now makes it possible for businesses to collect lots of data about the preferences and behaviours of their consumers (purchase/shopping history, websites they visited, products and services they were interested in etc.), in order to provide them with more personalized offers.

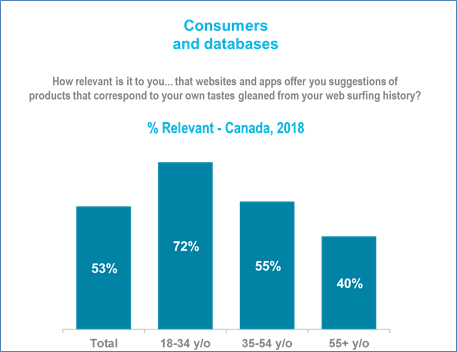

How relevant is it to you personally that, based on information compiled about you..., websites or electronic applications offer you suggestions of products that correspond to your own tastes gleaned from your web surfing history? (Very, somewhat, not very, not relevant at all)

To our surprise, this question radically divided the Canadian population almost into two equal halves. Just over one in two people in the country (53%) consider it "relevant" to have data collected about them for personalized offers, while slightly fewer (47%) see no relevance there and tend to oppose it.

The social divide is most acute by age group. While 53% overall consider it relevant to have data collected on them so they get personalized offers, this proportion rises to 79% among 18-24 year olds! It falls to 67% among 25-34 year olds, and declines in linear fashion to 39% among people aged 65 and over. Young people are more consumption-oriented and therefore eager to share their data to enhance their consumption experience.

What's more, the depth of young people's enthusiasm compared to their elders signals a major generational gap with respect to the sharing of personal data with third parties. The ethical issues surrounding the dissemination of this data seem to be of little concern to the younger generations but of great concern to older people.

People in Eastern Canada are more "wary" about this kind of data sharing. There is a "relevance rate" of 46% in the Maritimes, 48% in Quebec and 55% in the rest of the country (for a national average of 53%).

Among those most in favour, where we find a majority of young people (under 44), the cocktail of motivations is very broad. They strongly believe in the promise of personalization, which also exercises a remarkable symbolic function: anticipation. They believe and hope that the relevance of the content and offers they receive will give them access to the very best on the market, while also bringing out the very best in themselves through the stimulation the process provides. Self-improvement, a creativity boost, access to the best products/services and innovations, the pride of being early adopters, etc.: anything goes in terms of motivations and expressed needs.

The opportunities are immense for the companies and brands able to position their content strategy on customization. The above-list of hot buttons and values that companies and brands can respond to provides only a glimpse of what these personalization aficionados expect.

Conversely, the other half of the population who do not believe in the relevance of collecting their personal data probably see it as a manifestation of George Orwell's "Big Brother" (1984). They are watching us. They are spying on us. They are trying to sell us stuff that we don't really need and deliver messages that may be contrary to our interests, etc.

They are very critical of companies, holding them responsible for today's climate of uncertainty in which they are struggling to adapt. They are keen to maintain their freedom and control over their lives, and believe that third parties might be able to control them through the use of their personal data (Hollywood sci-fi movies probably serve to enflame some people's imaginations). They also subscribe to a form of voluntary simplicity and anti-consumerism (No Logo). Their opposition is ideological and philosophical.

The future of personalization

Personalization is here to stay, even as it infiltrates more and more areas of our lives. (CROP is also investing heavily in it by transforming its practices and business model.) What will give it momentum, what will ensure people embrace it, is its relevance. In our daily lives, we are constantly bombarded with mass messages that may have little relevance to us. The relevance of the content offered by personalization will be the key to its spread and its acceptance.

The challenge for companies and organizations is to ensure this relevance. But to do this, they need intimate knowledge about individuals; hence, the collection of personal data.

Even the personal data of the most resistant people. Because they tend to be very sensitive to the issue of environmental protection in particular, sending them relevant content on this issue might make them more receptive to personalization!